history of Malaysia

History of Malaysia- a Perspective

History of Malaysia- an overview

A reflection of its long history timeline that blends Asia’s vibrant ethnicities and cultures, modern Malaysia has made itself one of the most diverse countries. One of the Southeast Asia region’s fast-developing cities, the capital Kuala Lumpur, marvels with towering skyscrapers, together with its green parks and gardens. Enchanting tropical beaches and islands, while somewhere on the middle stretch of the spinal mountain range of Titiwangsa, Cameron Highlands lush tea plantations sat on a cool breezy mountain climate- an excellent relaxing destination, while the steaming humid rainforest of Taman Negara (National Park) offers millions of diversities yet to be discovered.

Malaysia’s historical timeline is an essential aspect of its cultural identity, from the ancient trade routes to the colonial era and beyond. Today, the country is a thriving hub of commerce, tourism, and cultural exchange, offering visitors a unique and immersive experience.

And for all that reasons (I believed), Malaysia defines the essence and the cream of Asia, where there is only one country, where all the colors, senses, flavors, and sounds of Asia blend together. Especially the three major ethnicities in Asia, the Malays, Chinese, and Indian, plus numbers of other Asian ethnicities freely hold on to their cultures and beliefs, offering myriad, which makes Malaysia Truly Asia.

Malaysia: Facts & Stats

| Head of States | Paramount Ruler: Yang di-Pertuan Agong |

| Head of Government | Prime Minister |

| Administrative Center | Putrajaya |

| Population | 33 million |

| Currency (Ringgit/RM/MYR | RM/MYR1 equals USD0.24 |

| Form of Government | Federal Constitutional Monarchy with two legislative houses (Senate- 70) | (House of Representative- 222) |

| Official Language | Malay (Bahasa Melayu) |

| Official Religion | Islam |

| Total area (Sq Km)/(Sq Mi) | 330,241/127,507 |

Malaysia: Ethnic Composition

| Malays | Chinese | Indian | Others |

| 69.8% | 22.4% | 6.8% | 1% |

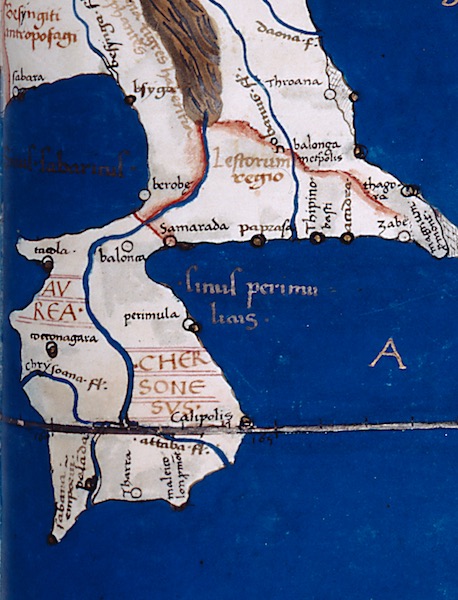

Ptolemy Map

One most intriguing and at the same time perplexing early accounts of South East Asia occurs in Geography, which has usually been ascribed to the Greek astronomer Claudius Ptolemy. The Golden Chersonese (Chersonesus Aurea) meaning the Golden Peninsula was the name of the Malay Peninsula used by the Greek and Roman geographers. The Malay people are being considered the Austronesian genome.

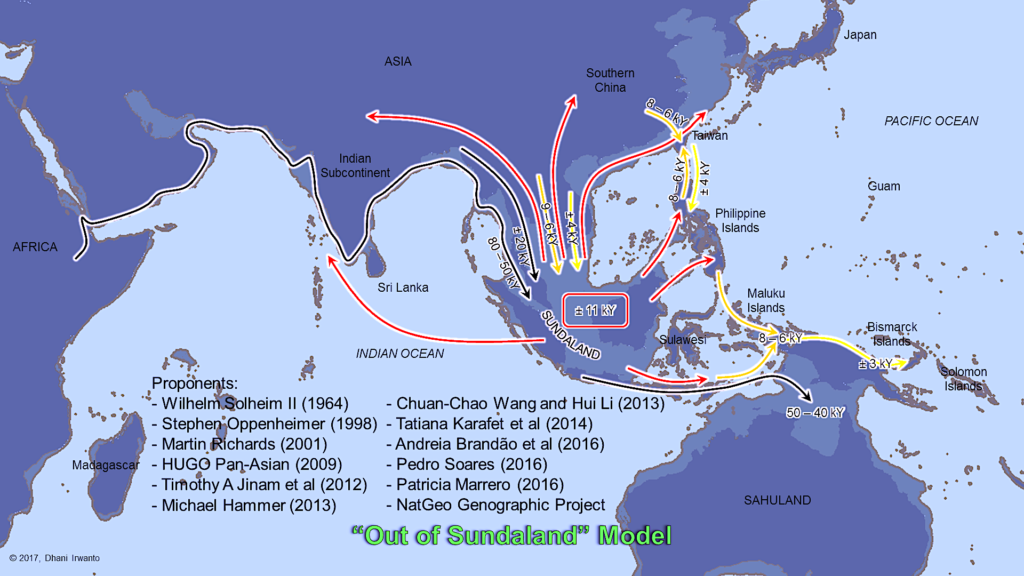

Origin of the Malays

The origins of the Malay people continue to be a subject of ongoing research and discussion. Over the years, various theories have been proposed, including the Yunnan theory (first published in 1889) and the Taiwan theory (published in 1997). These theories suggest that the ancestors of the Malays migrated from Yunnan and Taiwan to Southeast Asia. However, I tend to favor the more recent theory proposed by Stephen Oppenheimer in his book “Eden in the East,” which is supported by a number of local and international researchers. Another compelling theory is presented in Dhani Irwanto‘s book “Sundaland: Tracing the Cradle of Civilizations.” Both of these theories offer intriguing insights into the possible origins of the Malay people.

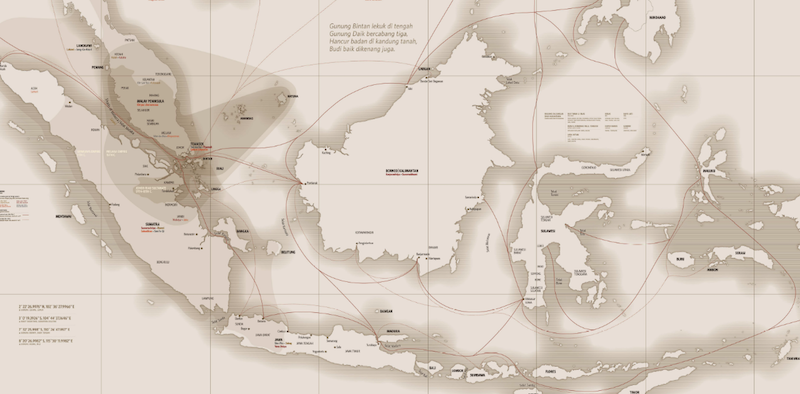

Prior to the establishment of the Malacca Sultanate Empire (14th-15th Century), the region encompassing the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, the Philippines, the southern region of Thailand, the Indonesian Archipelago, Timor Timur, and central south Vietnam (the Old Champa Kingdom circa 2nd Century until 1832) existed without defined borders. Traveling by sea, people would traverse great distances to visit each other for trade and other purposes. These interactions and cultural practices gave rise to the diverse culture and polity systems that define the region. The first united Malay Kingdom, Srivijaya, which dominated much of the Malay Archipelago, was documented through carvings on the walls of Borobudur.

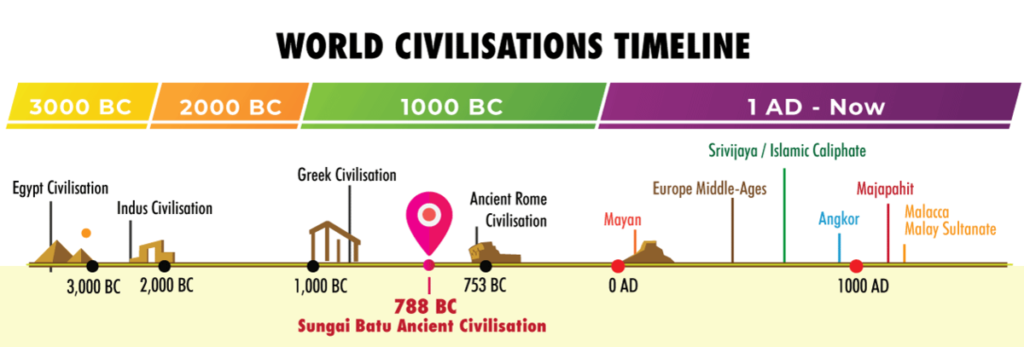

A remarkable and enigmatic archaeological site situated in the northern Peninsula Malaysia, overseen by the local university and led by Prof. Dato Dr. Mokhtar Saidin, has yielded a remarkable archaeological discovery at Sungai Batu in 2009. The evidence found suggests that the early Malay people possessed sophisticated knowledge, skills, and technology as early as 535 BCE, which predates the establishment of Ancient Rome, Borobudur, and Angkor Wat. As a result, Sungai Batu is now considered the oldest known civilization in Southeast Asia. At that time, this civilization demonstrated advanced iron smelting techniques on a large scale and exported iron ingots.

Hindu Buddhist Era (Indianization of Southeast Asia)

By looking at the map, this region of Southeast Asia (Peninsula, Borneo, Sumatra, Java, and others) easily show that the location is strategically located. Small Malay kingdoms already existed in the 2nd or 3rd century CE. It was the spices that became the key drivers of the Indianization of Southeast Asia. The time when the emissaries of Ashoka, the Buddhist mission of the Great Emperor Ashoka.

Another factor that drove this mission was the nomadic interference in Siberia (the source for Indian bullion) Indian traders and priests began traveling to the Malay Peninsula, which became its new source of gold, and soon the news spread to the world through a series of maritime trade routes. With them, the concepts of Hinduism and Buddha Mahayana were initially limited more or less to the upper class of the old Malay society-the royalty. Slowly it was also spread through intermarriage. While the commoners would often follow the religious faith of their rulers, there was also always an undercurrent of fear of evoking the wrath of their earlier animistic deities. Hindu Buddhists were assimilated only with a mixture of local theological beliefs. The most significant was the Hinduism temple ruins in the northern state of Kedah (refer to images above). Here is a list summary of Kingdoms in this region:

Western (European) Invasion

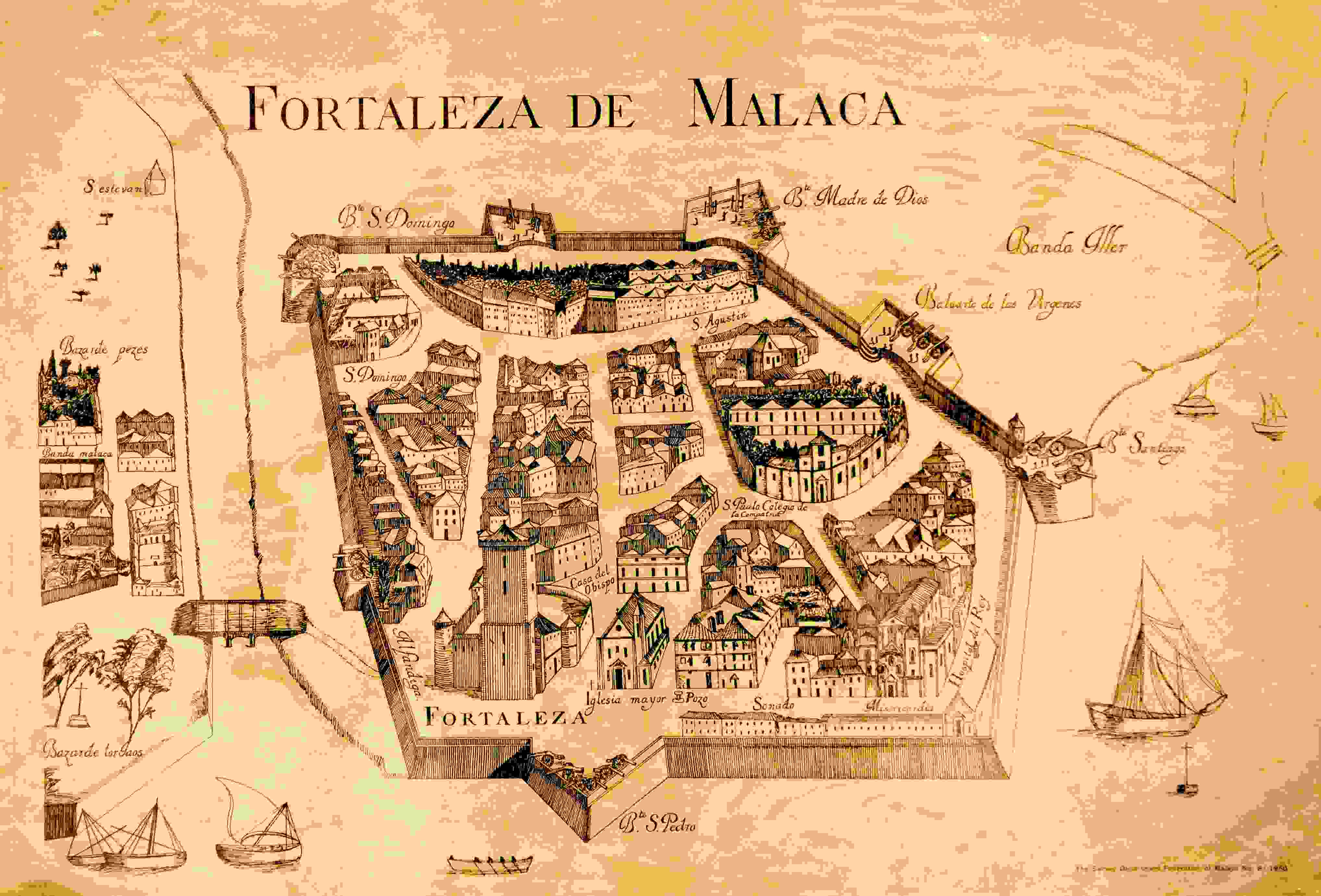

1511 Portugal

Portugal’s expansion plan was initiated by King Manuel 1 (O Venturoso) of Portugal (1495-1521) to beat Spain in the Far East together with Albuquerque‘s project of establishing firm foundations for Portuguese India, Hormuz, Goa, and Aden, to ultimately control trade and most importantly to weaken the Moslem shipping strength in the Indian Ocean. This wasn’t long after the completion of the Christian Reconquista where Andalusia fell to Queen Isabella 1 of Castile in 1492.

With a force of some 1200 men and about seventeen or eighteen ships, Albuquerque set sail to Malacca and set a number of demands, one of which was permission to build a fortress as a Portuguese trading post near the city. The Sultan refused all the demands. The conflict was unavoidable and the war lasted 40 days before the city of Malacca fell to the Portuguese on 24th August 1511.

Malacca Sultan fled to Pahang and then to the Johor-Riau archipelago. One of his sons became the first Sultan of Perak and numerous attack was launched to recapture Malacca from the Portuguese but failed.

Read more about the Capture of Malacca

1641 Dutch

Dutch marked the longest Malacca period under foreign control which is 183 years (1641-1825) with intermittent British occupation during the Napoleonic Wars (1795-1818). An era that saw relative peace with a less serious interruption from the Malay sultanates due to the understanding earlier forged between both the Dutch and the Sultanate of Johor-Riau in 1606. It was also the time that the importance of Malacca declined when the Dutch much prefer Batavia (Djakarta) as their economic and administrative base in the region and their hold in Malacca was to prevent the region’s loss to other European powers. Malacca ceased to be an important port, and the Johor-Riau Sultanate became the dominant local power in the region.

Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oostindiche Compagnie, VOC) in the early 17th century established trading bases in South East Asia, in 1619 the Dutch established themselves in Batavia (Djakarta), and in 1641 the Dutch allied with Johor, and they managed to capture Malacca after 6 months siege.

Read more about the Dutch in Malacca

| Status | Dutch Colony |

| Capital | Malacca Town |

| Common Language | Dutch, Malay |

| Governor | |

| * 1641-42 | Jan Van Twist |

| * 1803-18 | Hendrik S. van Son |

| Historical Era | Imperialism |

| Established | 14th January 1641 |

| British occupation | 1795-1818 |

| Relinquished by treaty | 1st March 1825 |

British in the Malay Peninsula- The Straits Settlement

Pulau Pinang (Penang) 1786

The British East India Company had been longing desperately to muscle into sea commercial trade territories that were dominated by the Dutch East India Company- VOC. They have been kept at bay throughout the 17th-18th century. However the cards change hands with their success in Indian colonies and the decline of the Dutch, and the English once again muscle their campaign to control the lucrative spice islands.

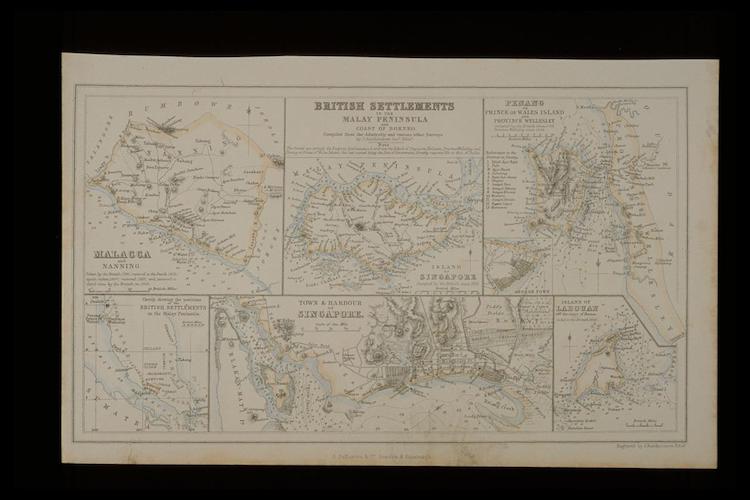

The first piece of Malay Peninsula land that become Britain’s territory was Penang Island. In 1786, three vessels led by Captain Francis Light occupied Pulau Pinang (the Island of Betel-nut). Inhabited the island was a small number of Malays and at that time the island was part of the Kedah state territory. The Kedah Sultan (Sultan Abdullah Mukarram Shah), hoping to get an alliance from the British East India Company to defend Kedah sovereign state against re-invasion by Siam (modern-day Thailand), agreed to a permanent lease of the island. On the other side, the English company has no intention at all to defend Kedah, left that point vague, and continues carrying the occupation of the island. The Sultan attempted to recapture the island but failed. And in 1791 was forced to cede Penang, and again in 1800, the strip of the mainland coastline of Kedah opposite the island, Perai later being named Province Wellesley, both in exchange for a certain sum of money annually.

Singapura (Singapore) 1819

When Malacca was handed back to the Dutch in 1815, British Governor at that time, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles eagerly look for an alternative.

An opportunity for Britain when the Johor-Riau-Lingga was in the Game of Thrones when 2 royal brothers were in a dispute over one of who had the right to succeed the last Sultan. Being aware of the dispute, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles struck a deal with Tengku Hussein Shah in Singapore, acknowledged him as the legitimate successor of Johor’s throne, and proclaimed him the Sultan of Johor. Fluent in Malay, and serving as assistant secretary to the Governor of Penang at the age of 23, Raffles was indeed familiar with the region’s history and culture. He eventually served as Lieutenant-Governor in Java and wrote the book ‘History of Java‘. He managed to convince the newly proclaimed Sultan Hussein Shah to sign an official treaty on 6th February 1819 to give the British East India Company the right to operate a trading post in Singapore. Both the Sultan and Temenggung Abdul Rahman (Governor of Johor-Riau-Lingga Sultanate) would earn a handsome sum of money to uphold the treaty.

The Dutch heard the wind about the English establishment in Singapore and this led both parties to sign the Anglo-Dutch Treaty in 1824. This also marked the separation of the big Malay archipelago that led to modern-day Indonesia and Malaysia.

Malacca 1824

The Dutch colony of Malacca was ceded to the British in the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 in exchange for the British possession of Bencoolen and for British rights in Sumatra. Malacca’s importance was in establishing an exclusive British zone of influence in the region, and it was overshadowed as a trading post by Penang, and later, Singapore.

Dinding

The Dindings — named after the Dinding River in present-day Manjung District — which comprised Pangkor Island, and the towns of Lumut and Sitiawan on the mainland, were ceded by Perak to the British government under the Pangkor Treaty of 1874. Hopes that its excellent natural harbor would prove to be valuable were doomed to disappointment, and the territory sparsely inhabited and altogether unimportant both politically and financially was returned to and administered by the government of Perak in February 1935.

In 1824 British hegemony in Malaya (before the name Malaysia) was formalized by the Anglo-Dutch Treaty, which divided the Malay archipelago between Britain and the Netherlands. The Dutch evacuated Malacca and renounced all interest in Malaya, while the British recognized Dutch rule over the rest of the East Indies. By 1826 the British controlled Penang, Malacca, Singapore, and the island of Labuan, which they established as the crown colony of the Straits Settlements, administered first under the East India Company until 1867 when they were transferred to the Colonial Office in London.

British Malaya-

Federated and the Un-Federated Malay States

Unlike the term British India, British Malaya is often referred to as the Federated and Unfederated Malay States, which were British protectorates with their own local Sultans, together with the Straits Settlements, which were under the sovereignty and direct rule of the British Crown, after a period of control under British East India Company.

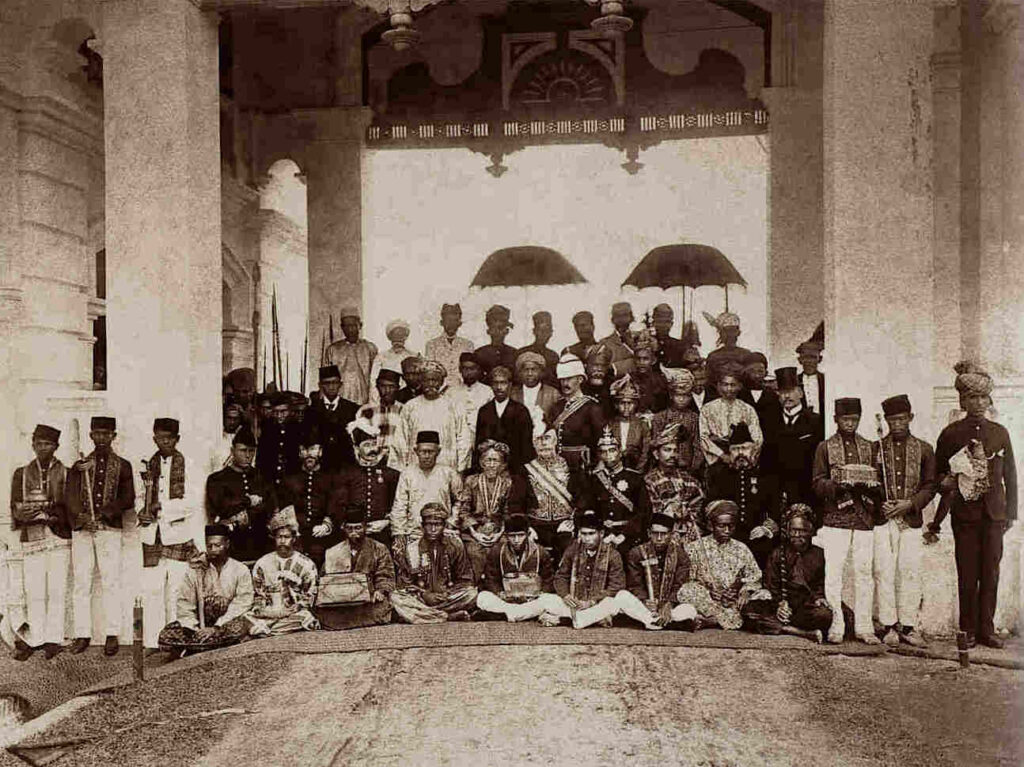

The British were reluctant to acquire other commitments in the region, but periodic forays by Siam (now Thailand) into north Malay states, piracy supported by Malay rulers, and periodic conflicts between Malay rulers of tin-producing states and Chinese tin miners mobilized by Chinese secret societies all threatened British commercial interests and prompted the British to become increasingly involved in peninsular affairs. In the 1870s, the British adopted a system of indirect rule over Malay states that furnished the beginnings of a centralized state. In 1874 the British agreed to recognize and support a contender as the sultan of Pangkor in exchange for the sultan’s acceptance of a British representative, or “resident,” whose advice would be sought and followed on all issues except Malay custom and religion. British residents were later established in three other tin-producing states, which became known as “protected states.” In 1896 the Malay rulers of these states and Pangkor signed the Treaty of Federation, which established the Federated Malay States. Malay rulers were invited to provide input into the federation’s development, but in reality, the new constitutional arrangements were designed to provide an appearance of Malay rule while effectively reducing traditional rulers to mere decorous bystanders.

To streamline the administration of the Malay states, and especially to protect and further develop the lucrative trade in tin-mining and rubber, Britain sought to consolidate and centralize control by federating the four contiguous states of Selangor, Perak, Negeri Sembilan, and Pahang into a new entity, the Federated Malay States (FMS), with Kuala Lumpur as its capital. The Residents-General administered the federation but compromised by allowing the Sultans to retain limited powers as the authority on Islam and Malay customs. Modern legislation was introduced with the creation of the Federal Council. Although the Sultans had less power than their counterparts in the Unfederated Malay States, the FMS enjoyed a much higher degree of modernization. Federalisation also brought benefits through cooperative economic development, as evident in the earlier period, when Pahang was developed through fiscal federalism, using fiscal equalization payment funds derived from the revenue of Selangor and Perak.

A different governing arrangement was established with other Malay states that were more independent of British control than the Federated Malay States. Siam tenuously controlled the northern countries of Kedah, Terengganu, Kelantan, and Perlis until a 1909 convention between Britain and Siam placed those countries under British influence.

The sultans of these states refused to join the confederation, but they did accept British advisors. Unlike residers, the counsels had no effective superintendent power and reckoned on tactfulness with the sultans for policy matters. The southern state of Johor also remained fairly independent of British influence until 1909, when the sultan accepted a British “ fiscal counsel ” with wide-ranging powers. therefore, by 1914 the Malay Peninsula was composed of 10 political realities the woe agreements, four Federated Malay States, and five Unfederated Malay States.

Initially, the British followed a policy of non-intervention in the relationship between the Malay states. The commercial importance of tin mining in the Malay states to merchants in the Straits Settlements led to infighting between the aristocracy on the peninsula. The destabilization of these states damaged the commerce in the area, causing British intervention. The wealth of Perak’s tin mines made political stability there a priority for British investors, and Perak was thus the first Malay state to agree to the supervision of a British resident. British gunboat diplomacy was employed to bring about a peaceful resolution to civil disturbances caused by Chinese and Malay gangsters employed in a political tussle between Ngah Ibrahim and Raja Muda Abdullah. The Pangkor Treaty of 1874 paved the way for the expansion of British influence in Malaya. The British concluded treaties with some Malay states, installing “residents” who advised the Sultans and soon became the effective rulers of their states. These advisors held power in everything except to do with Malay religion and customs.

Johore alone resisted, by modernizing and giving British and Chinese investors legal protection. By the turn of the 20th century, the states of Pahang, Selangor, Perak, and Negeri Sembilan, known together as the Federated Malay States, had British advisors. In 1909 the Siamese kingdom was compelled to cede Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, and Terengganu, which already had British advisors, over to the British. Sultan Abu Bakar of Johor and Queen Victoria were personal acquaintances and recognized each other as equals. It was not until 1914 that Sultan Abu Bakar’s successor, Sultan Ibrahim accepted a British adviser. The four previously Thai states and Johor were known as the Unfederated Malay States. The states under the most direct British control developed rapidly, becoming the largest suppliers in the world of first tin, then rubber.

This period of slow consolidation of power into a centralized government and compromise—the Sultans retained their reign but do not rule in their states—would have a great impact on the later road to nationhood. It effectively marked the transition of the idea of Malay states from a collection of separate lands governed by their own different feudal rulers, toward a federation with a Westminster-style constitutional monarchy. This became the accepted model for the future Federation of Malaya and ultimately Malaysia, distinguishing the nation throughout the Asian continent, whereby most other countries adopted stricter, heavily centralized unitary state administrations.

Read more about British in Malaya

The Second World War 1941-1945

The First World War did not affect Malaya directly, aside from a naval skirmish between the renegade German cruiser SMS Emden and the Russian cruiser Zhemchug off the coast of George Town, in what became known as the Battle of Penang.

The Second World War however consumed the country. Japan invaded Malaya in 1941, as part of the coordinated attack that started at Pearl Harbor. Malaya and Singapore were under Japanese occupation from 1942 until 1945. Japan rewarded Siam for its cooperation during this period by giving it the state of Perlis, Kedah, Kelantan, and Terengganu. The rest of Malaya was governed as a single colony from Singapore.

After Japan’s surrender at the end of the Second World War, Malaya and Singapore were placed under British Military Administration.

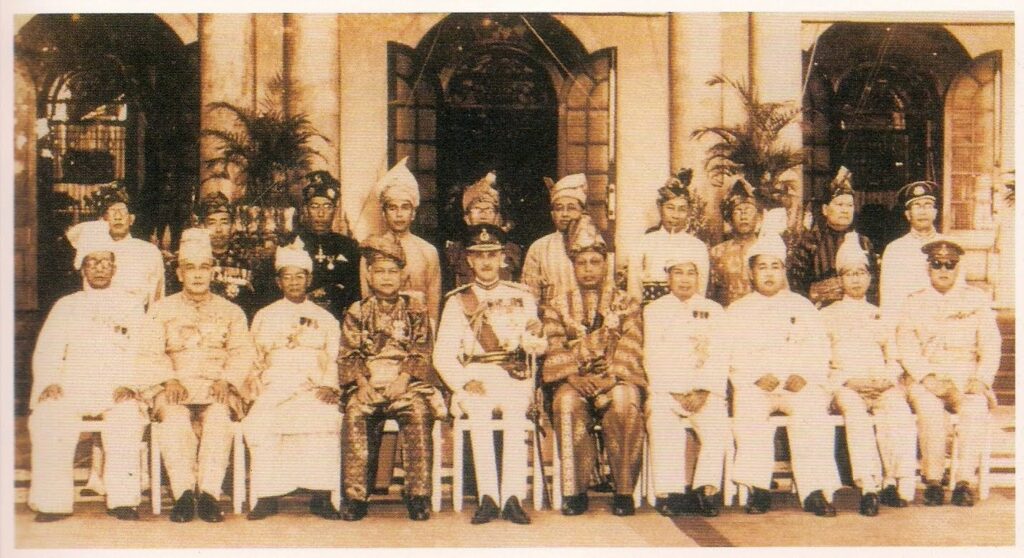

Declaration of Independence

The Malayan Declaration of Independence (Malay: Pemasyhuran Kemerdekaan Tanah Melayu Jawi: ڤمشهوران كمرديكاءن تانه ملايو), was officially proclaimed on 31 August 1957, by Tunku Abdul Rahman, the first chief minister of the Federation of Malaya. In a ceremony held at the Merdeka Stadium, the proclamation document was read out at exactly 09:30 a.m. in the presence of thousands of Malayan citizens, Malay Rulers, and foreign dignitaries. The proclamation acknowledges the establishment of an independent and democratic Federation of Malaya, which came into effect on the termination of the British protectorate over nine Malay states and the end of British colonial rule in two Straits Settlements, Malacca, and Penang.

The document of the declaration was signed by Tunku Abdul Rahman, who was appointed as the nation’s first prime minister. The event is celebrated annually in Malaysia with national day Hari Merdeka.